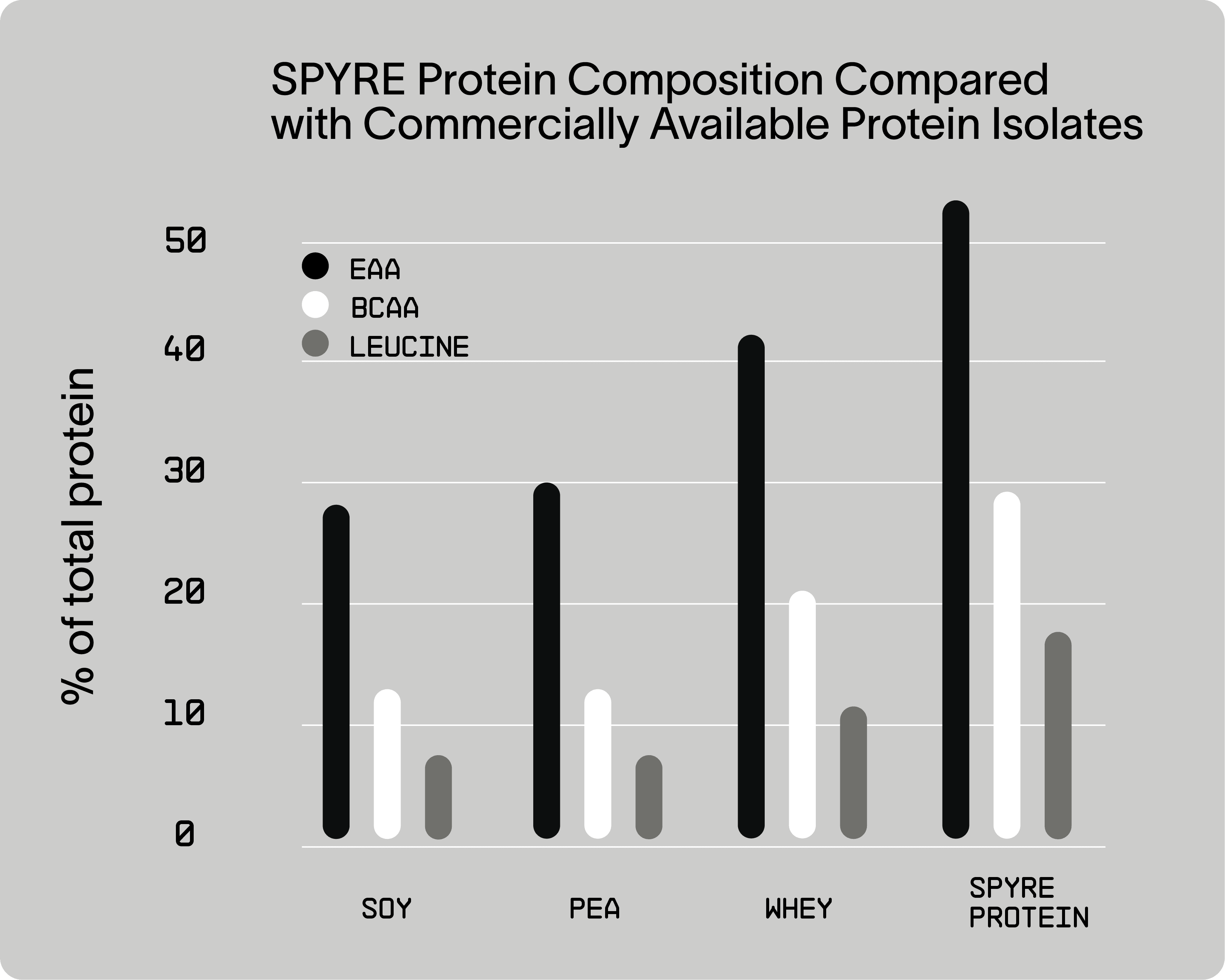

A recurring question among athletes and fitness enthusiasts is how to optimize nutrition timing to support strength, endurance, and recovery. While protein timing has long been debated, recent evidence suggests that the type and composition of amino acids — particularly Essential Amino Acids (EAAs), Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs), and Leucine — are more critical determinants of Muscle Protein Synthesis (MPS) and performance adaptation than precise timing alone.

Essential Amino Acids (EAAs) Are The Foundation for Muscle Synthesis

EAAs — comprising nine amino acids the body cannot synthesize — are fundamental for muscle repair and adaptation. Unlike whole protein intake, EAA supplementation provides the direct substrates required for MPS.

A pivotal study by Børsheim et al. (2002) demonstrated that ingesting 6 g of EAAs one and two hours after resistance exercise significantly improved net muscle protein balance, effectively shifting the body from a catabolic to an anabolic state. The authors also showed that EAAs alone—without non-essential amino acids—produced this strong anabolic response, confirming that EAAs are sufficient and dose-dependent in stimulating muscle recovery and growth.

Building on this, Churchward-Venne et al. (2012) found that even a small EAA dose (~6.25 g) containing about 3 g leucine could maximize post-exercise MPS when paired with other amino acids, highlighting leucine’s role as the “trigger” amino acid for initiating synthesis (Churchward-Venne TA et al., Am J Clin Nutr, 2012).

For athletes with longer or multiple daily sessions, additional EAA intake — such as 5–10 g during extended workouts or a similar dose before training — may help maintain amino acid availability and support sustained adaptation. Across training types, ensuring sufficient EAA intake in the post-exercise window and throughout the day remains the most reliable strategy to stimulate and maintain muscle protein synthesis.

Branched-Chain Amino Acids (BCAAs): Context Matters

BCAAs — leucine, isoleucine, and valine — comprise ~35% of muscle protein and are oxidized

directly by skeletal muscle.

While BCAA supplements remain popular, evidence shows they cannot independently stimulate maximal MPS. Jackman et al. (2017) demonstrated that BCAAs alone elevated MPS only modestly compared with a full EAA mixture.

However, Shimomura et al. (2006) found that 5–10 g BCAAs taken before or during exercise reduced muscle soreness and central fatigue in endurance athletes, likely via reduced serotonin synthesis and ammonia accumulation.

For optimal support, take 5–10 g of BCAAs in a 2:1:1 ratio of leucine:isoleucine:valine before training, and the same amount during long or high-volume sessions. Post-workout supplementation is less critical if overall protein or EAA intake is sufficient. BCAAs are best used as a complement to complete EAA or protein sources, especially for athletes training fasted or following low-EAA diets.

Leucine: The Anabolic Trigger

Leucine is the most potent anabolic amino acid because it directly activates the mTORC1 signaling pathway, the body’s main muscle growth switch. Studies show that taking about 2–3 grams of leucine per serving is enough to fully stimulate muscle protein synthesis in most adults.

Research by Katsanos et al. (2006) demonstrated that an essential amino acid (EAA) blend with a higher leucine concentration (about 2.7 g leucine) significantly increased MPS in older adults compared to a lower-leucine formula, suggesting that leucine-rich intake is especially important for those with age-related declines in muscle responsiveness. Further studies, such as Norton et al. (2009), found that taking leucine-rich meals or supplements every 3–4 hours throughout the day helped maintain elevated MPS levels — a concept known as “leucine pulsing.” This approach ensures that the body repeatedly receives enough leucine to keep muscle-building pathways active, making consistent leucine intake a powerful strategy for promoting recovery, growth, and long-term muscle maintenance.

Altogether, research shows that consistent, high-quality amino acid intake matters more than rigid timing windows. Leucine, in particular, serves as the key anabolic trigger; consuming around 3 grams per serving activates the muscle growth switch of the body that drives muscle protein synthesis. While specific pre- and post-exercise dosing protocols can provide sustained fuel for recovery and growth, the most reliable strategy remains ensuring sufficient EAA and Leucine intake throughout the day. Further, BCAAs can further support performance when taken at 5-10g before or during high-volume sessions, though they are most effective when combined with complete EAA or protein sources — especially for athletes training fasted or on low-EAA diets

References

Børsheim, E., Tipton, K. D., Wolf, S. E., & Wolfe, R. R. (2002). Essential amino acids

and muscle protein recovery from resistance exercise. American Journal of

Physiology–Endocrinology and Metabolism, 283(4), E648–E657.Churchward-Venne, T. A., et al. (2012). Leucine content of a complete meal directs peak

activation but not duration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mTOR signaling.

American Journal of Physiology–Endocrinology and Metabolism, 302(1), E286–E295.Jackman, S. R., Witard, O. C., Jeukendrup, A. E., & Tipton, K. D. (2017).

Branched-chain amino acid ingestion stimulates myofibrillar protein synthesis following

resistance exercise in humans. Frontiers in Physiology, 8, 390.Shimomura, Y., Murakami, T., Nakai, N., Nagasaki, M., & Harris, R. A. (2006). Exercise

promotes BCAA catabolism: Effects of branched-chain amino acid supplementation on

skeletal muscle during exercise. Journal of Nutrition, 136(6), 1583S–1587S.Katsanos, C. S., Kobayashi, H., Sheffield-Moore, M., Aarsland, A., Wolfe, R. R. (2006).

A high proportion of leucine is required for optimal stimulation of the rate of muscle

protein synthesis by essential amino acids in the elderly. American Journal of

Physiology–Endocrinology and Metabolism, 291(2), E381–E387.Norton, L. E., et al. (2009). The leucine content of a complete meal directs peak

activation but not duration of skeletal muscle protein synthesis and mammalian target of

rapamycin signaling in rats. Journal of Nutrition, 139(4), 743–749.